In October, global markets remained positive, with the Nasdaq technology index and emerging markets (MSCI Emerging Markets +4.2%) clearly leading the way. With the exception of China, which fell 3.9% due to weak domestic demand, the gains were led by countries such as Korea (+24.5%) and Taiwan (+10.8%), thanks to companies linked to artificial intelligence (AI) and semiconductors.

In the United States, strong third-quarter corporate earnings boosted stock market gains. In Europe, although growth remains very weak, the market managed to advance 2.46% thanks to the momentum of the automotive and luxury sectors.

For its part, the Fed lowered interest rates by 0.25%. However, Chairman Powell warned that there are no guarantees of further cuts in 2025, which increased volatility.

- S&P 500: +2.27%.

- Nasdaq: +4.77%.

- Stoxx Europe: +2.46%.

- All Country World Index EUR: 4.34% (the dollar rose 1.68%, the index in USD rose 2.18%).

- Global fixed income index EUR: +1.54% (the dollar rose 1.68%, so the index in USD advanced 0.60%).

To get an idea of the uncertainty generated by trade tensions, we need only recall what happened on the day Trump threatened to further increase tariffs on China: the S&P fell 2.7% and the MSCI World fell 2.3%. Everything calmed down once Trump and Xi Jinping reached an agreement whereby the US committed to reducing tariffs, while China would resume soybean purchases, lift restrictions on rare earths[1], and strengthen control over fentanyl.

It seems that we are reliving what happened last year: the market is rising again, led by technology and semiconductor companies, especially those most closely linked to artificial intelligence (AI).

If you recall, in February of this year, the Chinese AI company Deepseek rose to fame. It is dedicated to the development of large language models (LLMs) and associated tools, very similar to those of OpenAI (creator of ChatGPT). Its main appeal was its low development cost, which highlighted the valuations of similar companies or those linked to the same sector, such as Nvidia, which fell 17% that day. It seemed that the AI euphoria had come to an end, but the reality was quite different: shortly afterwards, the market forgot this news and Nvidia has since risen more than 100% from its lows.

And not just Nvidia. The group of AI-related companies in the United States[2], listed in an ETF that includes 43 companies, has risen on average by 80% in just seven months from those same lows. Is the average increase for 43 companies really 80% in just seven months? Maybe I’m too old, but is this really healthy? Those who bought Nvidia would say yes, of course. I, however, have my doubts. This is not a criticism of Nvidia; in fact, I consider it to be a very well-managed company from a fundamental point of view.

On average, 80% means that there are companies that have done even better: Celestica (+413%), Advantest (+273%), and Doosan Enerbility (+247%). In fact, we would have to go down to 28th place to find Nvidia in the ranking of rises. I will comment on this later, but you can already imagine where this is going.

Therefore, there is not only euphoria surrounding the “Magnificent 7,” but practically everything related to artificial intelligence. Of course, within this universe there are high-quality companies with solid, well-managed business models, but there are many others that are rising by contagion, simply because their name or activity is reminiscent of the same thing.

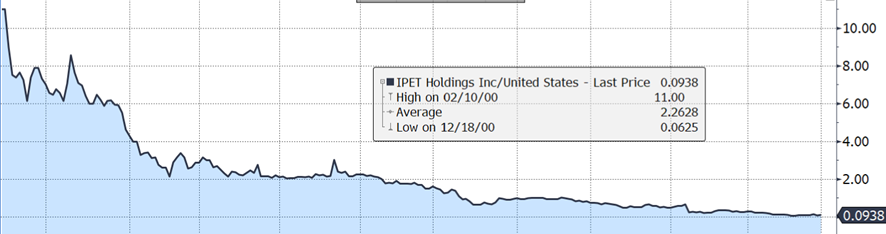

This is nothing new. I remember that during the dot-com bubble of 2000 (yes, it’s true, I was working at the time), there were companies that added .com to their name and automatically skyrocketed on the stock market. One example was Pets.com, an online pet food store, which rose 27% on its first day of trading and went bankrupt a year later.

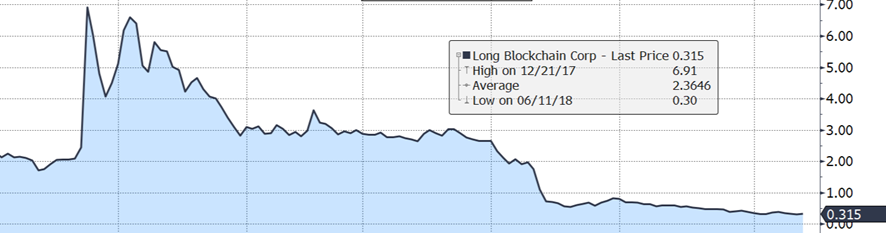

Something similar happened more recently, in December 2017, when a non-alcoholic beverage company decided to change its name to Long Blockchain Corp and on the same day its share price shot up 200%. Shortly afterwards, it was delisted from the Nasdaq for lack of transparency and it was discovered that it had never had any connection with blockchain.

PETS.COM

Source: Bloomberg

LONG ISLAND ICED TEA

Source: Bloomberg

With all of the above in mind, I would like to dwell on something I mentioned earlier: is this rise really healthy? Thanks to the quarterly letter from the American fund manager Wedgewood Partners[1], I think I understand it a little better.

They begin by quoting a sentence from Michael Cembalest of JP Morgan Asset Management that I find very revealing:

Oracle shares rose 25% after OpenAI promised it $60 billion a year—an amount that OpenAI does not yet earn—to provide cloud computing services that Oracle has not yet built and that will require 4.5 GW of power (the equivalent of 2.25 Hoover dams or four nuclear power plants), in addition to increased debt for Oracle, whose debt-to-equity ratio is already 500% compared to 50% for Amazon, 30% for Microsoft, and even less for Meta and Google. In other words, the technology capital cycle could be about to change.”

Why do you say that the capital cycle is about to change?

The capital cycle is the amount of investment required in a given sector at certain points in time. For example, in the oil sector, the capital cycle depends, among other things, on the price of oil: when the price rises or is expected to rise, oil companies begin a new investment cycle to take advantage of those expectations of increases.

Some sectors are more capital-intensive, meaning they need large investments to operate (such as energy or infrastructure), while others require much less capital. Until now, technology has been in the latter group. This characteristic explains why technology companies have higher than average market margins: their costs are lower and, as a result, the valuation multiples at which they trade are higher, as long as these margins are sustainable over time (and this point is key).

We have already seen this in previous comments: the S&P currently trades at around 25 times earnings, while the technology sector trades at 40 times.

Now, is 40 times earnings too much to pay?

The answer, as a Galician would say, is: it depends. Are that growth and those margins sustainable?

And this is where the comments by Cembalest and the WedgeWood managers come into play, which I think are very accurate.

If the capital cycle in the technology sector becomes more demanding, i.e., if the business requires increasing investment, costs will rise and margins will tend to fall.

In this context, only companies capable of using capital very efficiently will be able to maintain their profitability, although even for them it will be difficult to maintain current margin levels.

Why might this change occur?

- Excessive spending on AI infrastructure.

Tech companies are spending enormous amounts of money to build data centers, purchase chips (GPUs), and secure sufficient electrical power to train AI models. In a sense, they are building before knowing whether there will be enough real demand to justify these investments.

- From low capital intensity to high capital intensity.

This is a key change because it will determine who can bear these costs. Until recently, big tech companies (Google, Meta, Microsoft) were not very capital-intensive, meaning they did not need to spend too much on factories or physical infrastructure:

their value came from software, advertising, or digital services. With AI, that changes.

Now they need gigantic infrastructure to buy millions of chips, build data centers, and consume enormous amounts of energy.

This makes them very capital-intensive companies, something unthinkable just a few years ago.

And beware: this could make them more like industrial or energy companies, with more leveraged balance sheets and a heavier cost structure.

- Accelerated depreciation of hardware.

The chips (GPUs) used to train AI are extremely expensive and also become obsolete very quickly. Every year, Nvidia launches a new, more powerful generation, forcing companies to continually renew their hardware. In accounting, these machines are depreciated over 3 to 5 years (their costs are spread out over time), but in practice, they are no longer fully useful after 1 or 2 years.

This means that in the coming years, technology companies will have to recognize many accounting expenses, which may reduce their future profits (even if they continue to generate cash).

- Debt financing.

As the expenditure is so high, many companies can no longer finance it with their own money alone. In 2025, it is estimated that technology companies will have issued more than $157 billion in new debt to continue building infrastructure.

Meta, Oracle, and xAI (Elon Musk’s company) are taking out loans with extremely high debt levels (more than 60% leverage). Some are even using the chips they have purchased as collateral for the loans (like mortgaging a car to buy another one).

This turns the AI boom into a credit story: it depends on banks and debt markets continuing to lend cheap money. If rates rise or investors lose faith, the house of cards will come tumbling down.

- Energy Dependence.

Each new data center requires enormous amounts of electricity.

For example, a single Meta data center in Louisiana consumes as much energy as the entire city of New Orleans in the summer.

This is a real problem because power grids are not equipped to handle that level of demand, and energy costs are skyrocketing. In addition, local governments and regulators are beginning to limit the expansion of these infrastructures for environmental and capacity reasons.

Conclusion: The growth of AI will not depend solely on money or talent, but also on available energy and political decisions: where construction is permitted, what tariffs are applied, or what environmental impact is considered acceptable.

Phew, it doesn’t seem so attractive anymore, does it? Well, once again, it depends.

AI is here to stay, and when used properly, it will make many production chains and numerous jobs more efficient and therefore more productive. And productivity, in the end, is the most important ingredient for real wages to increase, as long as politicians curb their tendency to waste money.

AI is undoubtedly a powerful tool, but it has to be a good servant and not a bad master.

There will be winners, just as there were in the early days of the internet, when many companies fell by the wayside for various reasons—euphoria, leverage, lack of common sense—while others managed to run their operations prudently and consistently.

But if we realize that trading at more than 40 times earnings is not sustainable, and that the scenario outlined above—higher costs, lower growth, and pressure on margins—is real, then it stands to reason that valuations will eventually adjust. Multiples will fall to more reasonable levels, without this meaning that companies will cease to be good companies. They will simply reflect a more balanced environment.

Could the hype surrounding AI be leading us into another bubble?

I don’t know, but after researching the evolution of small and medium-sized enterprises, I get the feeling that there may be some speculative hype in the market.

Why do I think this? As I have mentioned on previous occasions, at Altum we invest in companies whose operations and/or practices do not conflict with the social doctrine of the Church, and the result of applying these filters generates a bias towards small and medium-sized companies.

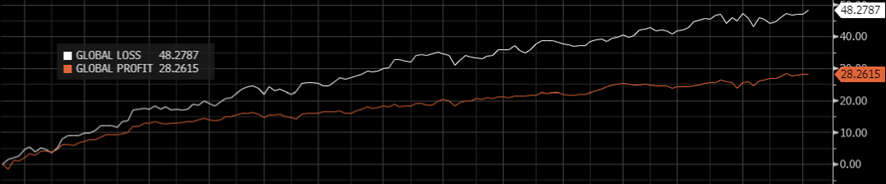

The Bloomberg World Small and Mid Cap Index has risen by 36% between April 4 and October 31, 2025, similar to the S&P. Our investments have not risen as much, which begs the question: why?

To understand this, I separated the companies on the list into those that were losing money and those that were making money. I was very surprised. The companies that were losing money rose by +48%, while the profitable ones rose by +31%. A difference of +17%.

That realization gave me a lot of peace of mind. At Altum, we focus on finding companies that make money, because that is the key ingredient for good long-term returns. We don’t want to participate in this speculation. At Altum, we prefer to build on rock.

Source: Bloomberg

That realization gave me a lot of peace. At Altum, we focus on finding companies that make money, because in the long term, that is the key ingredient for good returns.

That’s why I feel there is a speculative component in the market, the consequences of which will be painful for those seeking stratospheric returns in the very short term. It may be working for them now, but “Which of you, if you want to build a tower, does not first sit down and calculate the cost to see if you have enough to complete it?”[4]

For previous market commentary, click here.

[1] This is the name given to the chemical elements essential for the manufacture of mobile phones, computers, screens, electric vehicles, wind turbines, weapons, chips, and artificial intelligence components, among other things. China controls 60% of global production.

[2] Measured by the ETF iShares AI Innovation and Tech Active (BAI US)

[3] Wedgewood Partners Third Quarter 2025 Client Letter If You Build It Will They Come?

[4] Luke 14, 28-29